Today is July 4 and instead of thinking about pool parties and barbecues, I’m pondering the origins of this nation that we call the United States of America. Lest you think that I’m overly obnoxious for bringing up historical matters on what is traditionally the most celebratory holiday of the year, there is a reason for my preoccupation.

For several years I have been an amateur genealogist, researching my family history and learning what I can about our lineages. I’ve discovered that both my paternal and maternal ancestors came to this country very early in its establishment. On my mother’s side, many of the initial immigrants were from the Palatine region of Germany, desperately trying to escape war, poverty, and persecution, between the years of 1710 and 1750. They were some of the earliest settlers of Pennsylvania.

Massachusetts Bay Colony

My paternal side—the Stearns family—came even earlier, during the Pilgrim settling of Massachusetts in 1630. Not on the famous Mayflower, which landed in 1620, but on the Arabella, which embarked on April 12, 1630, from Nayland, England. This group was funded by the Massachusetts Bay Company by royal charter from King Charles I to officially engage in trade in New England. Sailing on the Arabella were, among others, Sir Richard Saltonstall, Governor John Winthrop, Edward Garfield (the ancestor of President Garfield), and—my ancestor—Isaac Stearns.

Obviously, any accounts of European colonization are complicated and biased, depending on who is doing the retelling, so I won’t attempt to weigh in the moral aspects of this land grab. What was unique about the Massachusetts Bay Company members was how they went about establishing their freedom. When King Charles I issued the charter, he neglected to add the stipulation that company members had to stay in England to conduct their meetings, which was standard protocol so that the Crown could control the efforts of the colony. Even before they left England, the Company decided to take advantage of this omission and elected to move the entire company to New England. According to the book The Charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony:

“The men reasoned that if they company continued to meet in England, the king could find things to quarrel about and could possibly take back the charter. This had happened to the Virginia Company of London. Taking the charter with them to America would remove much of the king’s power to interfere in their affairs. The company could erect a self-governing religious commonwealth. It would allow the leaders to create the kind of society they wanted, a ‘City of God in the wilderness.’”

The War for American Independence

It is believed that the whole of the Stearns family in the United States stems from the three Stearns men that sailed on the Arabella to help establish the Massachusetts Bay Colony: Isaac Stearns along with nephews Charles and Nathaniel. Certainly, by the time of the Revolutionary War in 1775, the Stearns descendants were plentiful enough to provide multiple generations to fight on the side of independence for America.

Among these soldiers them was Captain Josiah Stearns who commanded a company of fifty men from Lunenburg, Massachusetts in 1775. By 1776, he was a member of the Committee of Correspondence, with kinsmen Abijah and William Stearns. According to History.com, Committees of Correspondence “were emergency provisional governments set up in the 13 American colonies in response to British policies leading up to the Revolutionary War. The exchange of ideas, information and debate between different committees of correspondence helped organize and mobilize patriotic resistance in communities throughout the colonies and built the foundations for the Continental Congress.”

A different Isaac Stearns—(1750-1807) of Billerica, Massachusetts—was a sergeant in the Revolutionary Army. A delightful bio and story are included in the Genealogy and Memoirs of Isaac Stearns and His Descendants by Avis Stearns Van Wagenen written in 1901—yes I have a copy—relating the following:

“Isaac Stearns Jr was one of the minute-men who rallied at the first alarm, April 19, 1775, and was also one of the intrepid band of forty men, led by Ethen Allen, that took Fort Ticonderoga. He was a soldier in the siege of Boston for eight months and participated in the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Colonel Prescott and Sergeant Stearns stood side by side in the redoubt, as the British soldiers marched up the hill. The question was how near should they be allowed to approach for the fire to be most effective. The following conversation passed between them:

Col Prescott: ‘Stearns, are they near enough?’

Sergt. Stearns: ‘No, not yet.’

Col. Prescott: ‘Are they now?’

Sergt. Stearns: ‘Not quite.’

Then, after a little pause, Sergt. Stearns exclaimed, ‘There, that will do,’ and the order was given to fire, with the result so well known.”

As with all these types of sketches, their veracity is unknowable. Hundreds of years later, we are left with select archives like military records, tax lists, and oral histories with which to piece together what conditions were like in the early days of America. Certainly, these glimpses into the motivations and circumstances of the pilgrims, Puritans, and pioneers reveal the determined will of people looking for a better life for themselves and the will to sacrifice to create it. Freedom, after all, is not given, it’s earned, and often the price is more than any of us can imagine.

The Abolitionist

Permit me to jump forward a few hundred years to the period before the Civil War when the fight for freedom took on another aspect. I was pleased to find several abolitionists in the Stearns family tree, but there was one that was exceptionally notable.

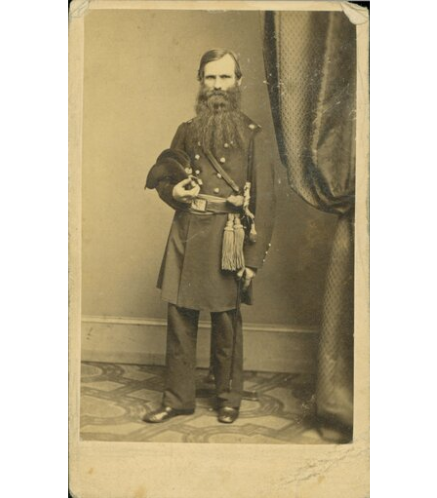

George Luther Stearns was born in Medford, Massachusetts on January 8, 1809, to Luther Stearns, a doctor, and Mary Hall, a Calvinist. History records him as a smart but unassuming child, forced by his father’s early death to work to support his mother and siblings. His career in business began with a profitable linseed oil manufactory for the shipping trade, but his fortune was made by establishing a lead pipe manufacturing plant in Boston.

Things get interesting in 1848 when George attended a political convention that resulted in the formation of the Free Soil Party which denounced slavery. In those early days, George was content to give money to people and groups that worked for the anti-slavery cause, but after a series of legislative acts in the mid-1850s, Stearns took on a more active role.

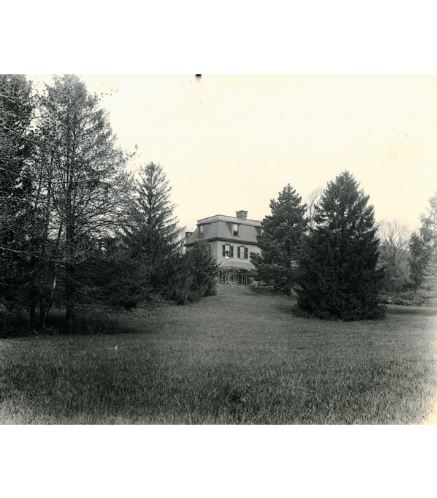

For years, the Stearns estate in Medford, Massachusetts, The Evergreens, was a stop on the Underground Railroad in aid of fugitive slaves. He was a confidant of prominent political and literary figures of the time, including Frederick Douglass, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Harriet Tubman, and Abraham Lincoln. He was also a funder of the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company, which sent Free State settlers to Kansas to ensure that it would vote to become a state free from slavery.

In 1856 George became the chairman of the Massachusetts Kansas State Aid Committee and met the charismatic abolitionist John Brown with whom he would have a troubled friendship. Stearns became one of a cadre of men called the “Secret Six” who helped to fund and arm John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, West Virginia in 1859. Brown and 21 other men attacked the Federal Armory at Harpers Ferry in the hopes of securing the weapons depot and arming slaves to start a revolt across the South. They failed, and John Brown was captured and hanged. Afterward, George Stearns was brought before Congress to testify about his involvement with the planning of the raid.

The defeat of Harpers Ferry did not dissuade George from his work on antislavery issues, and in 1861 he helped found the Boston Emancipation League which advocated for emancipation as “the only method of maintaining the integrity of the nation.” Soon afterward, Stearns was tasked with recruiting Black soldiers for the war, and it was primarily through his efforts that the first Black regiments in the North were raised: the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment and the 55th Massachusetts.

For more information on George Stearns and his efforts on the behalf of African Americans and other marginalized peoples, check out this fascinating article and video by Tufts University (who the Stearns family bequeathed The Evergreens to after George’s death). There is also this wonderful poem written to memorialize George’s death by John Greenleaf Whittier, and this quote by Ralph Waldo Emerson who spoke at the funeral: “[There is] hardly a man in this country worth knowing who does not hold his name in honor. . . . For the Spirit of the Universe seems to say: ‘He has done well; is not that saying all?”

Whatever this Independence Day means for you, pause and take a moment to remember the generations of men and women who lived and died to give us the freedoms we enjoy now. We may not know all of their names, but their struggles affected us all. Most, like Isaac and George Stearns, are absent from the history books but important, nonetheless. On this day, let’s celebrate their bravery and service.

Happy Fourth of July!

Main image is painting by John Trumball of Battle of Bunker Hill.

Wow! I was wondering what you discovered during your genealogical research, and just am so amazed at what you found. Such a fantastic family story, and American story. Thank you for sharing.