When you’re a kid, Halloween is a time for fantasy and fun. For a night you are encouraged to transform into another person or creature and roam the darkness with a pack of your friends. For the young ones, it’s exciting to consider the spectral realm: ghosts rising out of their graves, floating over the lighted streets and houses below. Kids embrace devils and demons as entertainment, not ever considering the reality of death. That is how it should be.

It’s only as we grow older and are haunted by the memories of people we’ve lost, that this time of year starts to carry other meanings. It’s interesting to me that the time we celebrate as Halloween has been marked for thousands of years by peoples around the globe as an opportunity to commune with the ancestors. There must be a reason for this.

During the Catholic celebration of All Souls Day, for instance, the poor of the congregation would go to the wealthy houses and receive cakes in exchange for praying for the souls of the family’s deceased relatives. The Celts believed that the boundary between the living and dead was at its thinnest during Samhain, so they dressed as monsters and fierce animals so that the fairies wouldn’t be tempted to kidnap them. The Mexican culture observes Dia de Los Muertos during which elaborate ofrendas are created to honor family members that have passed. Indigenous Guatemalans believed that once each year souls were allowed 24 hours to visit the living, so during the La Feria de Barriletes Gigantes grand kites are constructed to act as a beacon to help the spirits find their families.

Maybe it’s the proliferation of death and destruction that the world is dealing with right now that makes this holiday feel different. Or maybe it’s that even in my own small circle, a series of diseases, doctors, surgeries, and losses have permeated October. For me, what feels needed right now is going deep into the vulnerability of humanity and acknowledging the bloodlines of our ancestors. The spirits I want to spend time with are those who used their time on earth to bring love and joy. Those who came before to illuminate my path.

If you feel the need to spend these moments before the dark half of the year in fellowship with your family, spirit, or land ancestors, here are a few ways to honor them.

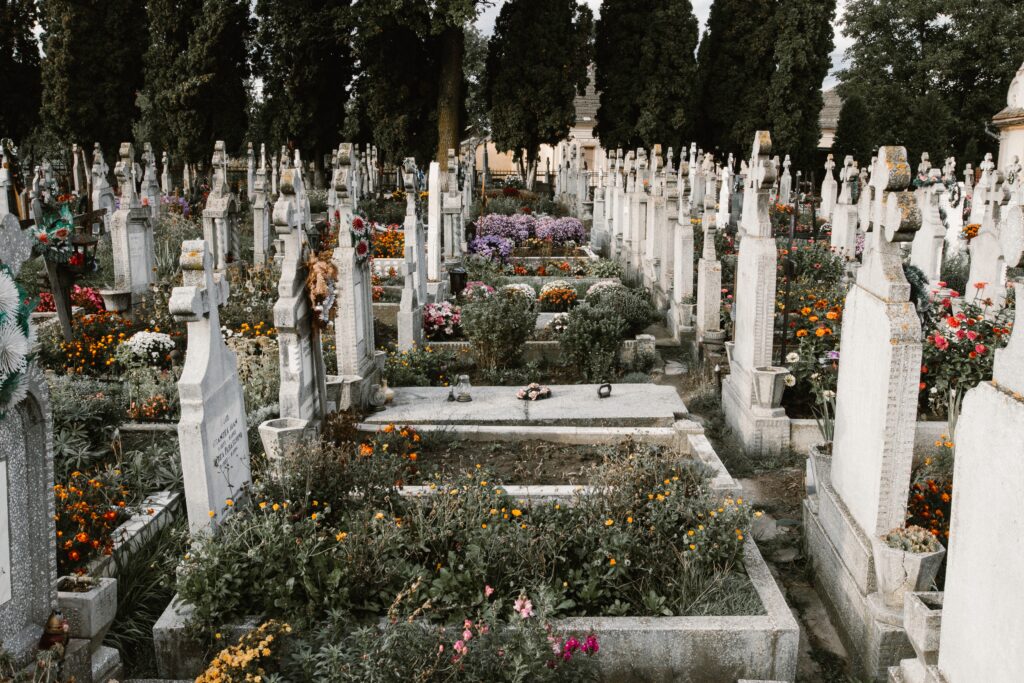

Visit their resting place.

Traditionally it was the living family’s responsibility to clean and maintain a loved one’s gravesite. In our modern American cemeteries this is rarely a necessity, though spending time in the area still serves a purpose. I love when I see families set up picnics by an ancestor’s gravestone, everyone eating and telling stories about the past. Fresh flowers and wind streamers are a nice touch too. Or pour their favorite drink out while listening to music and saying a soft prayer. When my mom died, we scattered her ashes in the ocean, and now whenever I’m in Hawaii, I make a point of getting into the water in that spot. There is something of her essence that remains for me there.

Build an altar.

In many cultures, it’s common to always have a family altar up in the house. Other people only set up ancestor areas in concert with holidays or birthdays. Regardless, these spaces can be as elaborate or simple as you wish. I’ve been in homes that have an entire room dedicated to those no longer with us and in which an offering of food and drink is replenished each day. Other people put flowers next to a picture on the mantel and call it a day. If you think about it, even the custom of hanging family portraits along a hallway can serve as a type of altar, giving visitors and relatives alike an immersive experience into their genealogy. During Halloween, it’s fun to introduce kids to this tradition by putting mementos alongside your seasonal decoration in the house. You’re already draping things in black and putting skeletons everywhere—introducing great grandma and grandpa as spirit guardians is no great leap.

Pay homage to your ancestral heritage.

In some ways it seems like the Earth is continually shrinking. Lands that were mysterious and inaccessible just a generation ago are now tourist traps. People scale mountains just to take a selfie at the top. Google Maps allows us to aggressively zoom in to neighborhoods and cities. Many historical properties have online real estate listings complete with pictures and room layouts. We have more information than ever before available about who we are related to and where our bloodlines come from. The question is: how do we take that knowledge and build a true connection?

Some lucky people will get to go on heritage quests and walk in the same places that their ancestors did. For the rest of us, it might be enough to research and create foods associated with our various cultures or ethnic groups. This year, my daughter and I are considering making either British Soul Cakes (a cross between a biscuit and a scone depending on the recipe) or trying the trickier Scandinavian aebleskiver pastry.

Spending time researching or updating your family tree is a good practice during this time too. Obviously, you can go full-on into this hobby, building detailed dossiers on relatives going back generations, but even sketching out the basics of the kin you have direct knowledge of can be cathartic.

Heal some trauma.

Speaking of catharsis, if you’re ready to delve deeper into your murky family origins I highly recommend the book “It Didn’t Start With You” by Mark Wolynn. This is not by any means a light read, but it has been blowing my mind. The basic premise is that we’re all carrying trauma caused by our family system, and sometimes behaviors are passed down by people we never even met.

“Not all behaviours expressed by us actually originate from us. They can easily belong to family members who came before us. We can merely be carrying the feelings for them or sharing them. We call these “identification feelings.” Mark Wolynn

Wolynn does a great job of connecting the physical—our DNA, the cells that will become the eggs of the grand-daughter existing within the grandmother—to the metaphysical. Wolynn showcases patient stories from his practice to illustrate how the twisted roots of someone’s depression, anxiety, pain, or phobias might be inherited rather than lived. He makes a very strong case for history repeating itself in countless generations unless the trauma response is healed.

The exercises introduced in the book are unlike any I’ve seen in a self-help book before. Each chapter builds on the previous in guiding you to construct what the author calls a “Core Language Map” made up of your Core Sentence, Core Complaint, Core Descriptors and Core Trauma. By building this Core Language Map, you’re doing the work of investigating family history to reveal the source of your inherited trauma and then giving you the tools to heal it.

Obviously, healing family trauma is the work of a lifetime, and isn’t tied to a certain period of the year. But there is something to be said for beginning this ancestor excavation during the slower time of winter which naturally leads to introspection.

Or you can just say screw it and eat a bunch of candy. Totally valid. However you choose to mark this time, give yourself the grace and space to get grounded before the busyness that comes with November and December. And remember the blessing that is each breath we take.

Main image by Gabriel Castles at Unsplash.